By Oyewole O. Sarumi

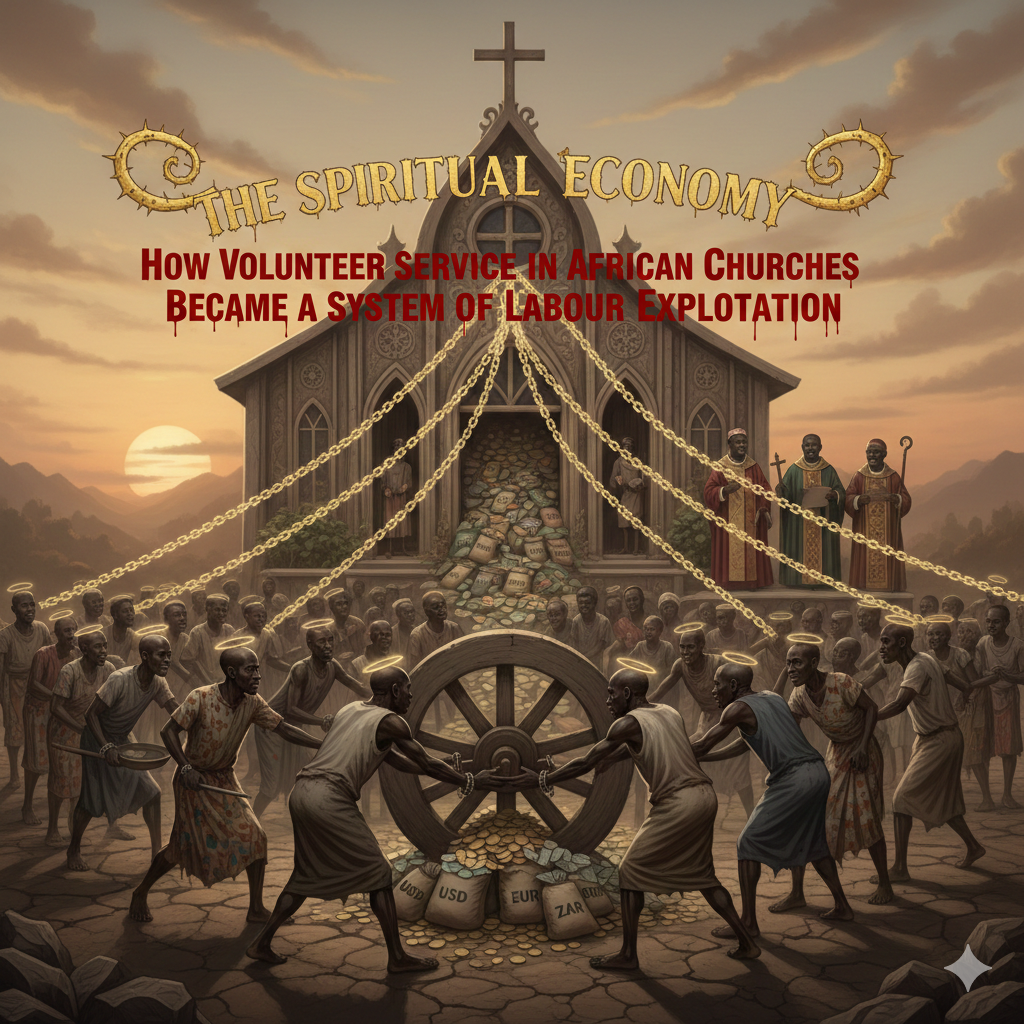

Across the African continent, a profound and troubling paradox defines the modern Christian ecosystem especially the pentecoastals and charismatics, but not limited to these two. Beneath the soaring roofs of megachurch auditoriums, amidst the polished production of televised broadcasts, and within the bustling administrative offices of spiritual empires, a vast, silent workforce labors.

They are the ushers, the choir members, the media technicians, the security personnel, the cleaners, children teachers, and the youth coordinators. Their work is essential, their hours are long, and their compensation is conspicuously absent, framed instead as a sacred offering unto the Lord. This is the unspoken engine of the African church’s meteoric growth: a systematic reliance on free labour, spiritually sanctified and culturally enforced.

While church brands expand into universities and broadcast networks, and pastors ascend lists of global wealth, the faithful are offered a celestial promissory note in exchange for their earthly toil. This article interrogates this spiritual economy, tracing how the biblical call to joyful service has been institutionalized into a mechanism of exploitation.

We will dissect the theological misapplications, the psychological conditioning, and the stark economic realities that sustain a system where the blessings of ministry flow overwhelmingly upward, leaving the foundational labourers with little more than the promise of a distant, heavenly reward.

The call is not to dismantle volunteerism, a noble Christian tradition, but to expose the line where voluntary service ends and systemic exploitation begins, challenging the church to embody the economic justice it proclaims.

The Architecture of Exploitation: From Service to Systemic Dependence

The model is now ubiquitous among the many church denominations that liters the African space. To sustain sprawling, multi-faceted operations that rival medium-sized corporations, African churches have constructed an elaborate architecture dependent on unpaid labour.

What begins as an invitation to occasional help, setting up chairs or handing out bulletins, evolves, for a dedicated core, into a relentless schedule. Volunteers commit five to seven days a week to rehearsals, program planning, digital content creation, facility maintenance, and administrative logistics amongst others.

These are not casual acts of charity; they are professional-grade roles. A young graduate editing high-definition sermon videos for a church’s YouTube channel, a skilled accountant managing weekly offerings and handles the whole accounting management, or a trained events coordinator orchestrating a major conference, all perform work that in any secular context would command a formal salary, benefits, and legal protections.

The institutionalization of this labour is the critical shift that I want to examine in this piece. The church has moved beyond benefiting from voluntary help to structurally requiring it as the bedrock of its operations. This creates a blurred ethical line when looked at critically.

The messaging, “Serve in the house of God, and He will bless you,” is potent and convincing. It spiritualizes economic transactions, transforming labour from a mutually beneficial exchange into a one-way test of faith.

The system is normalized through a culture that equates busyness with holiness and sacrifice with spiritual maturity. The result is a spiritualized shadow economy where the most valuable currency is not money, but demonstrated devotion, often extracted from those least able to afford it.

Theological Weaponization: Scripture in the Service of Extraction

The most powerful tool for maintaining this system is not administrative policy but theological framing. Leaders adeptly weaponize scripture to sanctify the extraction of labor. The go-to verse is Colossians 3:23-24: “Whatever you do, work at it with all your heart, as working for the Lord, not for human masters… It is the Lord Christ you are serving.” When scripture verses like this is presented in isolation, it becomes a divine mandate for uncompensated diligence, a command to ignore earthly employers (or the lack thereof). The heavenly reward is endlessly emphasized, while concomitant biblical principles of earthly justice are conveniently muted with more Bible verses cherry picking.

This selective hermeneutic creates a glaring contradiction. The very Bible used to exhort free labour is replete with mandates for fair compensation. 1 Timothy 5:18 bluntly states, “The worker deserves his wages,” a principle Jesus Himself affirmed in Luke 10:7. Leviticus 19:13 commands, “Do not hold back the wages of a hired worker overnight.” James 5:4 issues a terrifying warning to exploitative employers: “The cries of the harvesters have reached the ears of the Lord Almighty.” The prophet Malachi 3:5 names God as a swift witness against those “who defraud laborers of their wages.”

The theological sleight of hand is profound. The biblical narrative, which consistently pairs spiritual service with material provision, from God feeding Elijah via ravens to Paul arguing that apostles have a right to material support (1 Corinthians 9:7-14), is bifurcated. For the leadership, biblical principles of provision and blessing are claimed, often manifesting in private jets and luxury homes for them, their children and those within their inner circle. For the volunteer base, only the principles of sacrifice and heavenly reward apply which they should expect hereafter. This creates a theological caste system where scripture is not a guide for communal justice but a tool for legitimizing inequity as we can see today.

The Psychological Machinery: Manufacturing Consent for Self-Sacrifice

When we probe beyond theology, a sophisticated psychological machinery ensures compliance. This machinery operates on several levels:

- Spiritual Gaslighting and the Stigma of Mammon: To question the system is to reveal a spiritual flaw as some may portend even by my writing this piece. So, desiring fair compensation for skilled, consistent work is framed as being “led by mammon,” lacking faith in God’s provision, or being “unwilling to sacrifice for the Kingdom.” The volunteer is placed in a spiritual bind: advocate for biblical economic justice and be labelled carnal, or accept exploitation as proof of piety.

- The Cult of Personality and Unquestionable Authority: Many African megachurches are built around a singular, charismatic “Man of God” or “Daddy.” This figure is elevated to a near-infallible status where most of them are deified. His decisions, including operational and financial ones, become extensions of divine will. To question the labour model is not to critique a policy but to challenge God’s anointed, a taboo with social and, believers are subtly led to fear, spiritual consequences.

- The Promise of Access and Future Blessing: Volunteering is often sold as a pathway to visibility, networking, and eventual breakthrough. The unpaid media head hopes the pastor will notice his talent and connect him to a media mogul. The usher believes her faithfulness will position her for a miraculous job offer. The system runs on the fuel of aspirational faith, where present exploitation is endured as an investment in a future miracle mediated by the church’s leadership or other powerful people in the church for connection.

This psychological indoctrination is perhaps the most pernicious aspect of the whole game. It internalizes exploitation, making the volunteer a complicit agent in their own deprivation and manipulation, all while believing they are climbing a ladder of spiritual favour.

The Stark Contradiction: Megafaith and Micro-Compensation

The irony of this system is etched in chrome and marble. Investigative reports, such as one by Churchandstate.org.uk, highlight a global disconnect: while no African church as an institution may rank among the world’s wealthiest, their leaders feature prominently on lists of the globe’s richest pastors. Forbes has placed at least five Nigerian pastors in the top ten. Their ministries, sustained by free labour, generate revenue streams from tithes, offerings, merchandise, and paid conferences, funding assets like private jets, luxury cars, and sprawling estates.

This visible disparity creates a cognitive dissonance that the theology of sacrifice struggles to contain. The pastor preaches heavenly reward from a pulpit in a designer suit, after arriving in a convoy of luxury vehicles, to an audience containing volunteers who skipped a paid work shift to be there.

The message of “store up treasures in heaven” is undercut by the leader’s ostentatious storage of treasures on earth. The labour exploitation enables not just ministry growth, but a specific lifestyle, one exclusively available to the top tier of the spiritual hierarchy. The volunteer cleans the sanctuary; the pastor’s wife blogs about the interior design of their third home. The contradiction is not just economic; it is a crisis of gospel witness, making a mockery of the simple, sacrificial life of Christ that is so often invoked.

Beyond Africa: A Cautionary Tale in Global Context

This phenomenon, while pronounced in Africa due to socio-economic pressures and specific church growth models, is not entirely unique. It represents an extreme endpoint of a global tendency to spiritualize professional labour within religious organizations. The historical context is instructive. The medieval monastic model involved voluntary labour, but within a communal framework of shared poverty and explicit vows. Modern church volunteering often demands similar levels of commitment but without the communal safety net or the clarity of a chosen ascetic life.

Western church models, by contrast, often demonstrate a blended structure. They are frequently subject to the secular governance of non-profit law, requiring transparency and formal employment for core functions. While volunteers are essential for community and event-based roles, specialized, consistent, and leadership-driven work is almost always salaried. This is not merely a function of greater wealth; it is a theological acknowledgment that Galatians 6:6 (“Let the one who is taught the word share all good things with the one who teaches”) applies to all forms of essential service that sustain the teaching ministry. The African church’s challenge is to adopt this ethical framework without simply replicating the corporate blandness of some Western models; to create a uniquely African expression of church that is both spiritually vibrant and economically just.

A Path to Redemption: Reclaiming Dignity in Service

Any reform to be done is not only possible but biblically mandated. It begins with a fundamental reorientation: viewing the church not as a corporation leveraging free spiritual capital, but as a community called to model God’s justice. Concrete steps include:

- Conduct a Spiritual and Labour Audit: Churches must courageously audit their operations. Which roles are essential, skilled, and time-intensive? These must be transitioned to paid positions, even if part-time or stipend-based. The church budget must reflect the true cost of its mission, with human resources as a priority line item, not an afterthought.

- Develop a Theology of Dignified Labour: Teaching must rehabilitate the biblical view of work. From Genesis 2:15, where God puts Adam to work in the garden, to the Pauline epistles, work is dignified and deserving of fair reward. Sermon series must tackle James 5:1-6 and Malachi 3:5 with as much fervour as they do tithing and breakthroughs.

- Implement Radical Transparency and Governance: The era of the unaccountable “General Overseer” must sunset. Churches need independent boards, published financial statements, and clear policies on staff compensation and volunteer limits. Donations should not disappear into a black box that funds only vertical prosperity.

- Redefine Volunteering: True volunteering should be rotational, limited in scope, and focused on community-building (e.g., greeting, occasional event help). It should never be the default for skilled, ongoing operational needs. Celebrate volunteers without making their role a burden.

- Leadership Must Incarnate the Ethic: Reform is hollow if senior pastors live in obscene luxury. Leading by example means adopting a publicly accountable, modest lifestyle that prioritizes reinvestment in the community and fair wages for all church workers. The biggest proof of a theology is the life of the one preaching it.

From Exploited Service to Empowered Discipleship

The African church stands at a defining juncture. Its vitality, growth, and global influence are undeniable gifts. Yet, its witness is being corroded from within by a system that uses the language of heaven to justify earthly injustice. The spiritual economy of free labor is a theological failure and a pastoral betrayal. It takes the precious offering of a believer’s time and skill, a modern-day widow’s mite, and deposits it not into a treasury of communal good, but into the engine of institutional and personal aggrandizement.

The call to serve is sacred. The joy found in humble, communal work for God’s people is real, as the youth camp experience in the TCG website beautifully illustrates. But that joy is poisoned when the structure around it becomes extractive and unequal. The gospel liberates; it does not enslave with spiritual guilt. The early church’s solution to logistical inequity was not to exhort the Greek widows to pray harder, but to appoint and presumably support deacons to ensure fair distribution (Acts 6).

The path forward is a return to prophetic integrity. It is to hear the words of Jeremiah 22:13 as a chilling indictment: “Woe to him who builds his house by unrighteousness and his upper rooms by injustice, who makes his neighbour serve him for nothing and does not give him his wages.

”The African church must build its house on righteousness. It must honour the worker, dignify the labourer, and ensure that those who serve in the temple can also feed their families from the temple’s store. Only then can its message of heavenly reward ring true, untainted by the hypocrisy of exploited labour on earth. Only then will service be truly joyful, voluntary, and a genuine reflection of the God who is just, the God who sees, and the God who pays His workers in full.